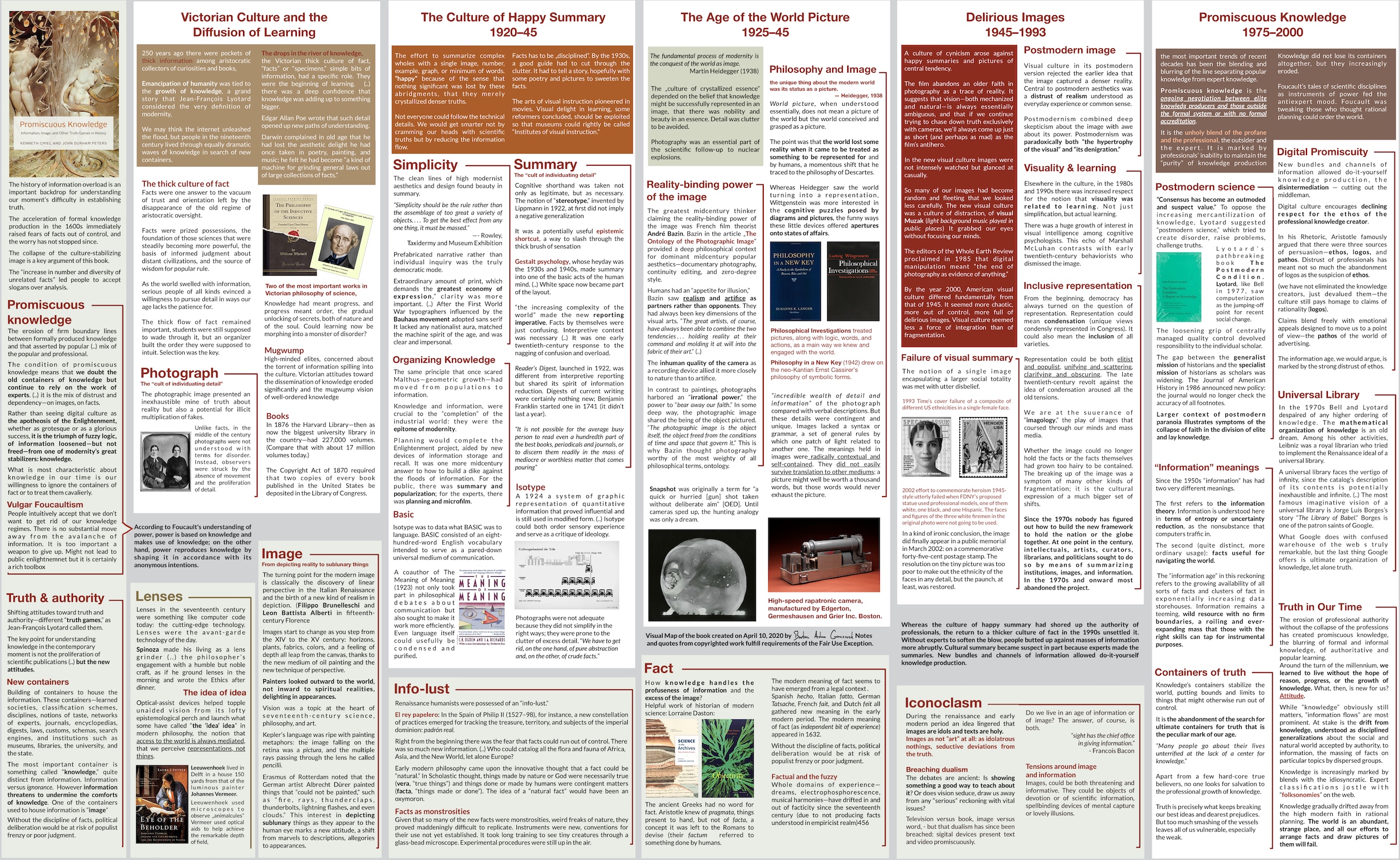

An account of the cultural and intellectual history of how Americans have lived with image and information since XXI century. It blends historical synthesis with insightful orienting narratives of eras, analyzing particular dimensions of them.

Continue ReadingHow might a digital whiteboard work as a thinking tool?

Interaction with “representations” on a whiteboard canvas can trigger learning processes. This phenomenon has been extensively observed and documented in child development.

Continue ReadingTell Your Story with Simple Visuals

Visuals enhance text-based communication. They provide a better way to spread ideas, explain concepts, and processes. No need to be a master designer. Here’s how you can share your observations visually in a very simple yet engaging way.

Continue Reading